Japanese surprise

It was inevitable that the Bank of Japan would adjust its monetary policy. At the time of Yield Curve Control (YCC), a central bank commits to price, not quantity. This means that when interest rates fall, as they did at the start of the corona crisis in 2020, the central bank has to sell plenty of bonds to ensure that interest rates rise in capital markets, just at a time when the market could use some extra liquidity. Now that has been several years back. At the moment, the problem is that interest rates are rising because of inflation (at 3.7 per cent at the highest point in 41 years) and as a result of yield curve control, bonds must now be bought up, which means that this is an easing (read stimulus) policy. Exactly the opposite of what is desirable and so, on balance, monetary policy is pro-cyclical instead of counter-cyclical. This contrasts quite a bit with the policies of other central banks, and that makes for a weaker yen. At one point, the yen was so weak that the central bank intervened by buying up the yen. That’s when policy did have to be adjusted. You cannot expand the money supply on the one hand (by buying up bonds and putting more yen into circulation) and support the currency by buying up the same yen on the other.

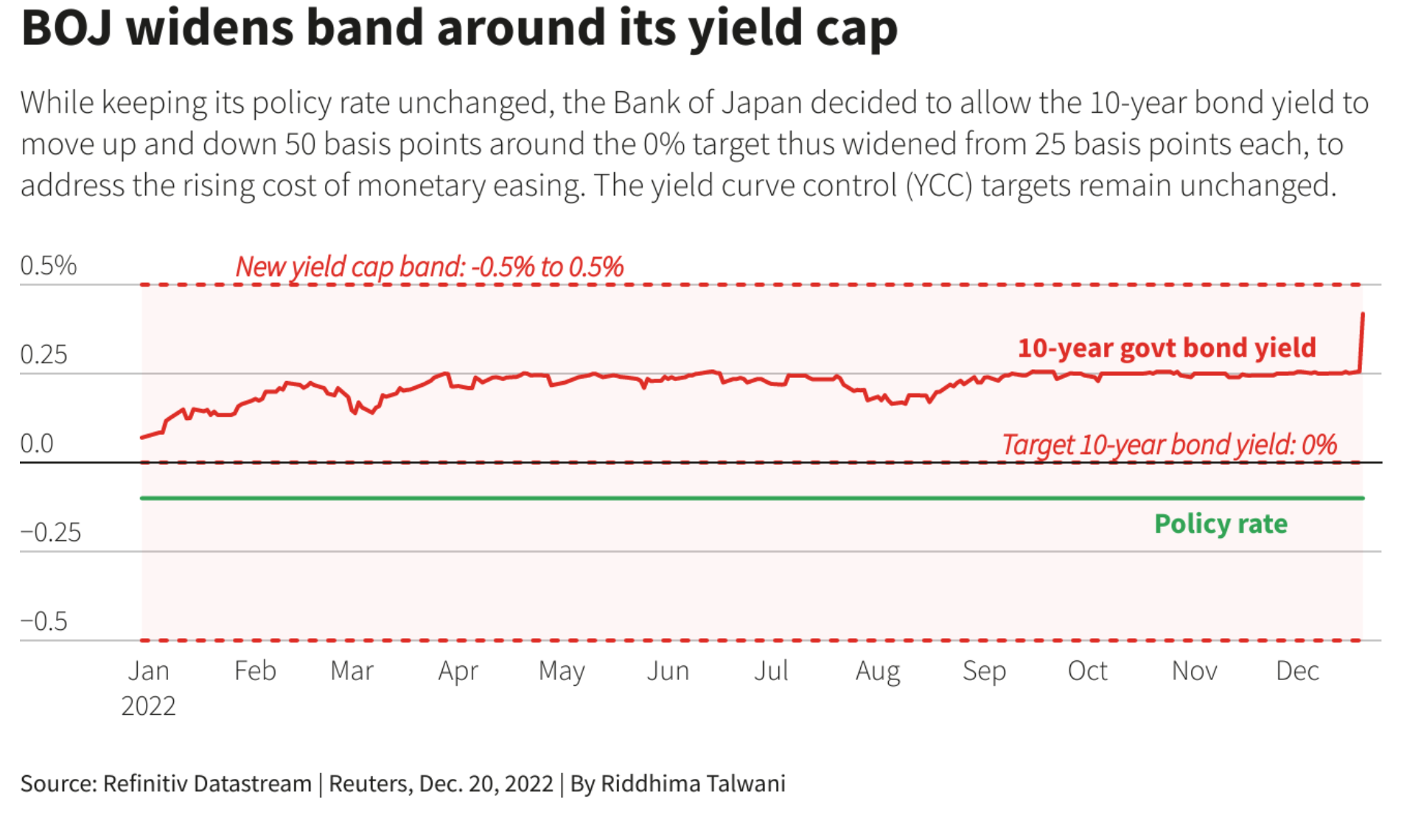

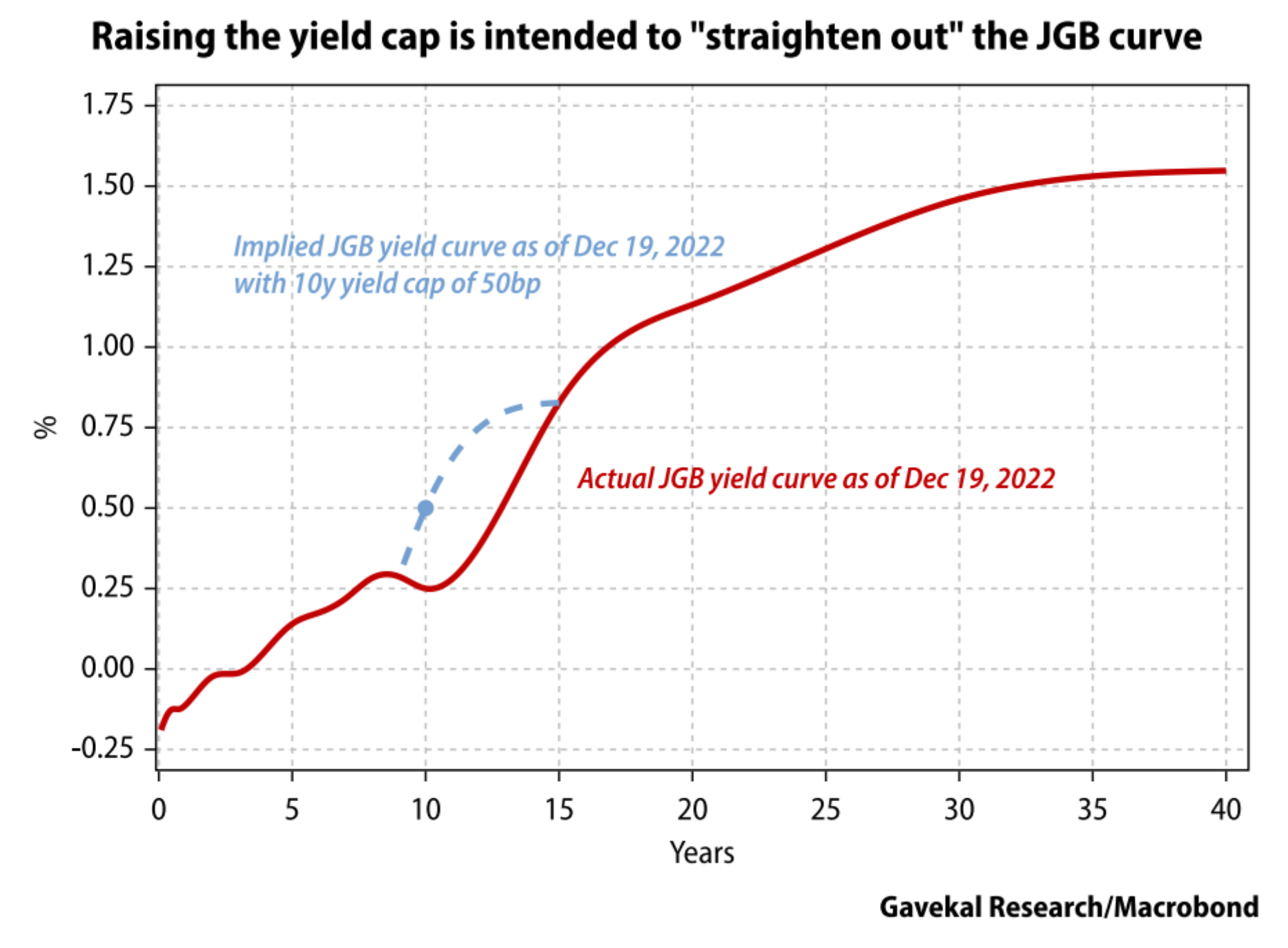

Knowing that this policy was finite, Kuroda decided to adjust it three months before his departure. Instead of 0.25 per cent for the 10-year rate, it will now be truncated to 0.5 per cent. Viewed in this way, it is a tightening measure, but at the same time it does give the Japanese central bank the ability to buy up more bonds, and so then there is an easing of policy. The immediate consequence is that there is no longer a strange kink in the Japanese yield curve. In fact, the BoJ is moving towards the market. Now that the BoJ has adjusted policy for the first time in a long time, more moves can be expected to follow, especially when Kuroda leaves in April.

The Japanese yen is one of the most undervalued currencies in the world. This makes everything in Japan cheap and has allowed Japan to gain market share from rivals such as Taiwan, South Korea and Germany in recent months. Authorities want a stronger yen. However, this does mean an end to Japan’s “long low” policy, which was the reason why the yen was so weak. Japanese investors (the proverbial Ms Watanabe) were borrowing in yen and deploying it in higher-yielding currencies. That money is now fleeing back to Japan. What these Japanese investors are selling are bonds in higher-yielding currencies, and this allows interest rates outside Japan to rise. A stronger yen is theoretically not good for Japanese equities, but compared to the past, this effect is small. Because for years the yen has remained relatively strong, many Japanese companies have decided to manufacture elsewhere in Asia (e.g. in Thailand). As a result, they have become relatively insensitive to adjustments in the yen. A steeper yield curve does benefit Japanese financials. Finally, this adjustment helps to depress the dollar.